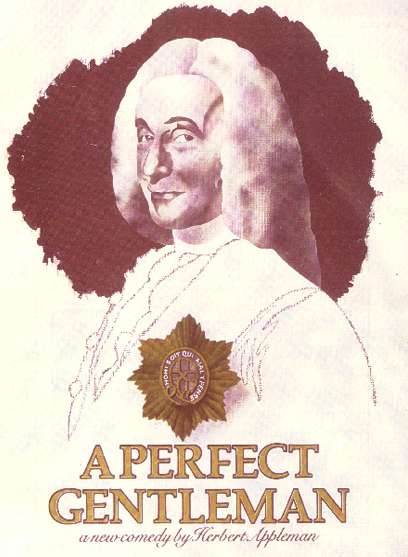

A PERFECT GENTLEMEN

A PERFECT GENTLEMEN

A comedy, set in London in 1755, about Lord Chesterfield, the noted English statesman & wit, who has great political ambitions for his illegitimate son, Philip; and Philip, who has very different ambitions for himself.

Winner, American Playwrights Theater Award

“A Superb Wit to Outshine Wilde”

— David Lewis, London

“Hilarious!” “Brilliant!” “Wonderful!” was the reaction of the audience to Herbert Appleman’s new play.

“Gentleman Triumphant at the Walnut”

— Nels Nelson, Philadelphia Daily News

“Gentleman Both Witty and Loving”

— Robert Butler, Kansas City Star

“Refreshingly Civilized”

— Roy Proctor, Richmond News Leader

Q: How did you, an American, happen to write a play about Lord Chesterfield?

A: I first came across Lord Chesterfield as an undergraduate. I was taking a course in English Lit and we were assigned The Letters to His Son. I read them and was horrified. Oh, my God. I thought, what a selfish and unfeeling old man, to put such terrible pressure on his son. Then, years later, after I’d married and had a son of my own, I had occasion to read “The Letters” again. Lo and behold, I now found myself sympathizing with Lord Chesterfield. He was obviously a good man who loved his son very much. It immediately struck me that since I could now identify equally with both father and son, this was a perfect subject for me to write about.”

Q: But if you wanted to write a father-son play, why didn’t you update things? Why did you stick to the 18th century background?

A: I was tired of the conventional modern play in which dialogue is usually reduced to grunts and curses, costumes range from blue jeans to no jeans, and the set is as dingy as possible. I wanted to write dialogue — or at least try, to the best of my ability — that was articulate and witty, for characters who could be dressed elegantly and presented in a setting — such as Chesterfield House — that was unashamedly beautiful. Before the advent of The Angry Young Men, the theater had, no doubt, prettified life too much; but in recent years the pendulum has swung too far in the other direction. I wanted to swing it back somewhat, to restore a balance, to remind the audience of certain civilized values that were now being neglected: not only the pleasures of good talk, lovely women, and beautiful things, but the virtue of compromise, the inevitability of imperfection, the possibility of conflict that doesn’t destroy affection and end in estrangement.

Q: How much of the play is quotation and how much has been invented by you?

A: For better or worse, 99 percent of A Perfect Gentleman is mine.

American Reviews:

A Perfect Gentleman Keeps Wilde Spirit Alive

Sunday Times, Trenton

by Tom Blackburn

Appleman’s A Perfect Gentleman currently at the Walnut Street Theater, reminds one of Wilde not only because everybody on stage tosses off epigrams like method actors toss off “uhs” and “ahs,” but because it goes right into the core meaning of mores and morals.

Chesterfield defends well the traditional virtues. His son doesn’t buy them. Young Stanhope rejects an arranged marriage to an older and wiser sister of the prime minister for love in a garret with an Irish governess, like himself an illegitimate child.

Not the smallest virtue of A Perfect Gentleman is that there is conflict from the time the servant announces the first visitor, but there’s no choosing of sides. In the end, Appleman and his characters reach an accommodation of viewpoints that will satisfy everyone but an ideologue. The production — a joint venture of the new Walnut Street Theater Company and the Virginia Museum Theater — makes the play’s virtues clear.

My notes on Michael Allinson, who plays Lord Chesterfield, link “cynical” and “doting father” in the first scene. This seeming contradiction never seems to be a contradiction because Allinson shows us Chesterfield from the start, with and without his wig, trying to replicate himself in his son not because he loves himself but because he loves his son.

I’ll admit I was wary of a play based on Lord Chesterfield’s letters, which were written to be read, not performed. I was wrong.

Appleman hasn’t so much used the letters (he says only 1 percent of the dialogue is from Chesterfield) as he has absorbed their spirit and then written a play in which Wilde could have taken pride.

Stylish, Touching Play is Just About Perfect

The Courier-Post

by Robert Baxter

Most students of English literature are familiar with Letters to His Son, those wonderful letters of advice and admonishment that Lord Chesterfield sent to his son, Philip. Appleman has taken those letters as the basis for a drama built around the conflict between Philip’s personal desires and his father’s ambitions.

A Perfect Gentleman may not be a perfect play but it comes very close. Appleman creates richly detailed characters, combines them in tender conflict and provides them with words that ring with style, with elegance and witty humanity.

Gentlemen Triumphant

Philadelphia Daily News

by Nels Nelson

Appleman has brought forth a virtually impeccable comedy of manners set in 18th-century London and just bursting with charm, style and well-turned witticisms.

There is a sensible ending, arrived at with good humor and a feather touch. A Perfect Gentleman has a universal message to offer fathers and sons who are at odds. And that is that love, both filial and paternal, is expressed in a great variety of ways, not all of them instantly perceived, and that the things each desires isn’t necessarily what the other is empowered to give.

A Perfect Gentleman

The Richmond News Leader

by Roy Procter

Appleman’s approach to dramatic conflict is so refreshingly civilized that it’s hard to recognize its great merit.

A Perfect Gentleman deals in sentiment without wallowing in sentimentality. It is that rare modern play — and thus can cast that rare spell — that is written out of the true sense of human love and accommodation and forgiveness, and its texture is summed up completely in its spellbinding final speech, in which Lord Chesterfield remembers his first encounter with Philip.

“You were wearing a full-length sleeping gown and a lace cap, and I — as befitted the occasion — was wearing all my decorations, including my Star,” he says as the spotlight isolates him on the stage.

“Catching sight of all those glittering ribbons, you smiled. I extended my finger and, without hesitation, you grasped it. I remember that your hand was warm and pleasant to hold … I don’t remember half as much about my first meeting with the king.”

Richmonders should bid such a loving play a fond farewell.

A Perfect Gentleman Both Witty and Loving

The Kansas City Star

by Robert W. Butler

If Herbert Appleman’s A Perfect Gentleman is not a perfect play, it is nevertheless a perfectly delightful one: a comedy that deftly juggles sentiment and wit, a quality all but forgotten in this world of TV sitcoms, within a beautifully evoked historic setting.

For its professional American debut, Missouri Repertory Theater and director John Reich have done the play justice dramatically and have perhaps gone even a step further technically. It may be worth seeing twice just to concentrate on Vincent Scassellati’s superb costumes.

Set in 18th-century London, A Perfect Gentleman depicts the efforts of the celebrated and now-retired Lord Chesterfield to turn his illegitimate son, Philip, into a budget version of himself by arranging for the young man to marry a well-connected widow, buying him a seat in Parliament and bribing the prime minister to give Philip an ambassadorship to Venice.

Alas, Philip is not a promising specimen. He is, in fact, a thoroughly ordinary fellow, what his father would call a “booby.” Therein lies the play’s universal conflict: the desire to please a parent while being true to oneself. That theme, and the love that binds generations, is examined by Appleman through superb use of language, a fine sense of irony and a genuine feel for the parent-child relationship.

It is language that sets A Perfect Gentleman apart and makes it very nearly unique in contemporary comedy. This is precision writing, the sort of dialogue so evocative of personality and circumstance that eye-popping costumes and sets could be dispensed with altogether without detracting from the play’s effectiveness.

London Reviews:

King’s Head

David Lewis

“Hilarious”, “Brilliant” and “Wonderful” was the reaction of the audience to Herbert Appleman’s new play on Monday night and that was only at the drinks interval. By the end of the show the well-deserved superlatives were flowing just as freely.

A virtually flawless first half sees an experienced cast devour some scintillating comedic writing, containing enough style and witticisms to put Wilde to shame.

Scene after scene hit home — Lord Chesterfield bribing the prime minister and instructing his son on the “high art” of approaching women, a cringing encounter between Philip and his betrothed, and the revelation that the bumbling son may not be all that he first appeared.

This clever turnaround sets the tone for a second act in which Appleman allows love and real feeling to challenge cynical posturing and politicking. The period costumes, in striking black and white, are given a modern twist, reflecting the notion that initial appearances are often deceptive.

Over the years the King’s Head has had its share of West End transfers. This play deserves to be another.

What’s On

by John Thaxter

For 30 years Lord Chesterfield, a busy statesman and literateur, seldom missed writing a daily letter to Philip, his shy and awkward son, offering him fatherly advice on etiquette, conversation and how to approach women. But when they were collected and published in 1774, Cowper described Chesterfield as a corrupter of youth, while Johnson thought his letters taught the morals of a whore and the manners of a dancing master.

Judge for yourself with his delightful new play by American writer Herbert Appleman who weaves Chesterfield’s dry wit and domestic life into a post-restoration comedy, providing a civilized and entertaining portrait of 18th-century high society, stylishly directed by Michael Friday.

Memorable set-pieces include Chesterfield’s verbal sparring with William Sleigh in a sharp cameo role as the corruptible prime minister, Elizabeth Counsell as the worldly widow attempting to bring Philip to the boil, and a scene in the boy’s lodgings when Chesterfield first comes face to face with Jacinta Mulcahy as his future daughter-in-law.

Not least of the evening’s pleasures are the designs by Charles Cusick-Smith, Chesterfield’s library setting giving on to a leafy garden, and superbly tailored period costumes in patterned monochrome.

Theaterworld Internet Magazine

Reviewed by Judith M. Steiner

Contemporary American playwright, Herbert Appleman, has written a post-restoration English comedy of manners set in 1755. Surprisingly, it works.

Appleman writes with enormous wit. The play is full of delicious and seriously good writing, spoken by a strong cast. Stacey’s sympathetic performance carries the show. Elizabeth Counsell as Lady Harrington gives a lovely performance.

In the end, this is a play about love: a father’s love for his son, and the cherished son’s love for his mistress, and his father, and his own son.

Greenroom-arts.com

by Kate Copstick

There is a small miracle to be observed at the King’s Head — it’s called A Perfect Gentleman and is a new comedy by Herbert Appleman.

Based on the letters between Lord Chesterfield and his illegitimate son, it is a finely told tale of marriages — political, of convenience, and in secret — and of fatherhood.

It is a rare genre — not a fringe play, but rather a miniature West End production.

A Perfect Gentleman is a perfect night at the theatre.